Bonnie Morin remembers everything about the day her son died.

She was making pork chops. Her son, 24-year-old Scott Morin, was pacing around the house. Her daughter, Sarah, 27, was upstairs. Scott walked into the garage. Then, Morin heard a bang.

"I heard a noise… I'd never heard a gunshot," she said. "I wouldn't know a gunshot, even today, if I heard it."

Morin thought one of her children had dropped something on her new kitchen floors. She opened the door to the garage to see if it was her son.

"When I opened the garage and saw Scott there bleeding, it was a very surreal moment for me. Very surreal," Morin said. "But I did save his life for a while."

What Morin saw was Scott lying on the floor of the garage, bleeding from a gunshot to his neck. Other witnesses saw the shooter fleeing the scene. Morin says she only saw her son.

"You know, they ask you what you saw," she said. "I didn't see anything. I saw my son. That's all I saw."

A critical care nurse, Morin's training took over. She kept Scott alive while they waited for paramedics to arrive.

It was that immediate care by Morin that would save a life – just not her son's.

'There's Never a Guarantee for Tomorrow'

Scott's shooting wasn't random. He'd arranged for someone to come sell him weed in his garage.

The deal went bad, and the dealer pulled a gun. Police eventually arrested a man for the shooting, but he was acquitted of Scott's murder.

"Not worthy to die for," Morin said. "Not a reason good enough. And I would gladly tell people that, you know, that this is what happens sometimes when you get involved in buying drugs. You don't know who you're buying from."

None of that was going through Morin's head, though, as she agonized in the hospital over the decision she was presented with: Would she agree to allow her son, now declared braindead, to be an organ donor?

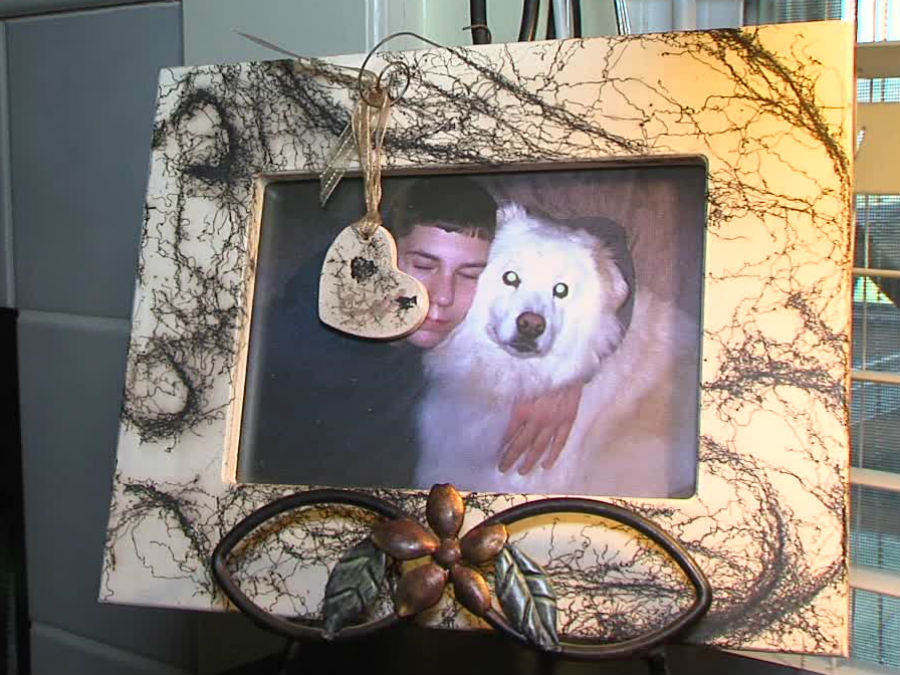

What she thought about was the chubby 6-year-old who finally thinned out around 12. Who developed a love for baseball and cars and the outdoors. Who, just a month before, had spent a final weekend together with her and their dog Bailey before he was put down.

"Bailey was 13 and he just couldn't get up anymore. Labor Day weekend, Scott and I spent the weekend with the dog. Scott would lift him up and take him outside, lift him up and take him out," Morin said. "Bailey was kind of mean and he had to wear a muzzle at the vet. And the last time, it was kind of funny – Scott's bringing him in and they're going, 'Bailey's walking!' He didn't have to be muzzled. Scott did make a comment, he said, 'Now don't you be biting the hand of Jesus.' That's what he told him before we had to put him down. They're buried together, now."

A month after Bailey died, Scott was shot. Even though he remained alive on life support for several days following the shooting, Morin says she knew the truth the moment she saw him in the garage.

"I was watching his breathing patterns," she said. "As a nurse, I saw it. As a mother, I didn't want to believe it. I saw it as a nurse … but as a mom, you don't want to believe that. But I knew right away he was not going to make it."

As a nurse, Morin had seen countless families struggle over the organ donation decision. Now as a mother, she faced it herself.

"It was still a hard decision. I knew I had to make it," she said. "I kept going back and forth, back and forth. I told Sarah, I told her dad, I said, 'He's not going to get better. I've seen it. He will not get better.' So I had to go from clinical to mother to clinical to mother. It was very difficult. I'm not sure it made it easier. It made me know more, and stuff you don't want to know."

'This is a Way He Stays Alive'

In the end, Morin said yes. Scott would become an organ donor.

There are eight organs that can potentially be recovered from donors: the liver, lungs, heart, kidneys, pancreas, and small intestine. In addition to organs, donors can also give skin, corneas, bone tissue, cartilage, heart valves and blood vessels.

Because of the location of his injury, and the amount of blood he lost, Scott was only able to donate one of his lungs. It went to a man in Michigan who shared his love of cars and the Detroit Tigers.

"One lung collapsed and he wasn't able to give it," Morin said. "His other organs they said didn't 'pink up' enough to go to a suitable donor. But the lung – which we all laughed at, because he was such a smoker – his lung went to a man about my age in Michigan."

Morin never met the man who received Scott's lung. But she did get a letter from him thanking her for all the things Scott's gift allowed him to do.

"I never met him. I never really … I always was crying. I just cried so much that it was very difficult for me to want any contact with him," Morin said. "Not that I begrudged him – I was happy he had a life. I was thrilled with it. In fact, I was exceptionally happy that Scott was able to do that for another human being; that through his death he was able to save another man's life. He did send me a letter that said he never would have been able to walk his daughter down the aisle at her wedding. Just his grandkids, the things he was able to experience because of Scott's gift, that he thanked me every day."

Sometimes people worry the families of organ donors don't want to hear from the recipients of their loved ones' organs, Morin said. But they do.

"That's the big thing, I think, with organ donations," she said. "Sometimes you find that the one who suffered the loss, you think they don't want to hear from you. But in truth, we do. We do. The thing with organ donation, and with anything, I've found, since losing a child, is that I want him to stay alive. This is a way he stays alive – through his memory. So if I'm crying it's not because I'm upset. I'm happy you're remembering."

Many Homicides, Few Donors

That Scott was able to donate even a single organ is amazing in and of itself.

Over the past 15 months, more than 200 Hoosiers became organ donors as a result of death. Only six of them, across the entire state, were homicide victims. Of those, five came from Indianapolis – and that's in a year in which 149 people were killed.

Doctors don't take chances when it comes to organ transplants – already a risky procedure – so if they're concerned about the viability of an organ, they won't let a transplant move forward.

"In order to be a donor, your heart has to be beating and you have to be in the hospital," said Dr. Tim Taber, the medical director of transplant nephrology for IU Health and chief medical officer for the Indiana Donor Network. "There's nothing inherent in a homicide that would make an individual not a donor. But in our experience, most homicide victims don't get to the hospital, aren't maintained or we're not able to support their bodies while the family decides to proceed with organ donation."

Taber has been performing transplants for 20 years. He says even though more transplants are being performed than ever before – IU Health alone did 521 of them in 2016 – the supply of available donor organs can never keep up with demand.

"In this country there are over 120,000 people who are on the list to receive an organ transplant," Taber said. "In Indiana it's well over 1,000. We do maybe a third of those patients a year. So we just can't catch up. As quickly as we're able to provide an organ for a recipient, there's another recipient who goes on the list."

What doctors like Taber have on their side is the enormous impact even a single donor can have. An individual donor who is able to donate all eight transplantable organs can save a potential 50 life years.

"I think donor families are truly heroes," Taber said. "I mean, on the worst day of their lives, when their loved one has unexpectedly died, they have a decision to make in many cases – and that's whether their loved one will be a donor. And donor families said yes."

More than 3.7 million Hoosiers are already registered organ donors. Registering is as simple as checking a box at the BMV; or you can do it online through the Indiana Donor Network.

But even if you are already registered – especially if you're already registered – Taber says you should talk about the decision with your family ahead of time, so they know your wishes.

"I hope that people talk about this today; that they talk to their family in the light of the day so they don't have to make that decision on the darkest day of their life," Taber said. "I have talked to my family about this. They know how I feel. And I hope that other people will talk about this."

'The Difference It Can Make in Someone Else's Life is Immeasurable'

"It took me 8 months before I felt like I could crawl out of my hole and be useful," Morin says.

Now eight years after Scott's death, Morin's a stronger, happier person than she ever thought she could be in those first dark days. She volunteers for the Indiana Donor Network – the non-profit that helps coordinate organ donations and provides support to the loved ones of donors – and helps make quilts for the families of other victims who are now where she was. She and her daughter, Sarah, travel around the world. They're preparing for Sarah's wedding. Scott is never far from their thoughts.

Morin is retired from nursing now. Though she still lives in the same home where her son was shot on that day in 2009, she says she's not the same person.

"You can't come out of it the same," she said. "You have to be different. My thing is I don't sweat the small stuff anymore. Because you're here today, gone tomorrow. You don't know. There's never a guarantee for tomorrow."

To other mothers and fathers, and wives and husbands and children, who find themselves faced with that decision she had to make in 2009, Morin has this to say: Organ donation saves lives.

"I would never suggest [it's a silver lining] to anybody. Organ donation is a personal decision. It's what they believe it is," Morin said. "For myself, I don't view it as a silver lining. I don't even like that saying. For me, it was making a positive out of a negative. We had a negative situation. My son was not going to live. He would never be the same man he ever was, and I got a chance to turn that into a positive by giving his organs. I view it more that way: Changing a negative sign to a positive sign."

Scott's memory will live on, Morin says, in the family of the man who received his lung, and in her own family's hearts. Her own memories of Scott comfort her, too. She was able to be there right up to the end, she says.

"I saw him come into this world and I saw him go out of this world," she said. "My son knew I loved him, and I was able to tell him I loved him, too. To the last breath he took, he knew I loved him."

If you'd like more information about organ donation, or how to become a donor, you can visit the Indiana Donor Network's website or call them toll-free at 1-888-275-4676.

Jordan Fischer is the Senior Digital Reporter for RTV6. He writes about crime & the underlying issues that cause it. Follow his reporting on Twitter at @Jordan_RTV6 or on Facebook.